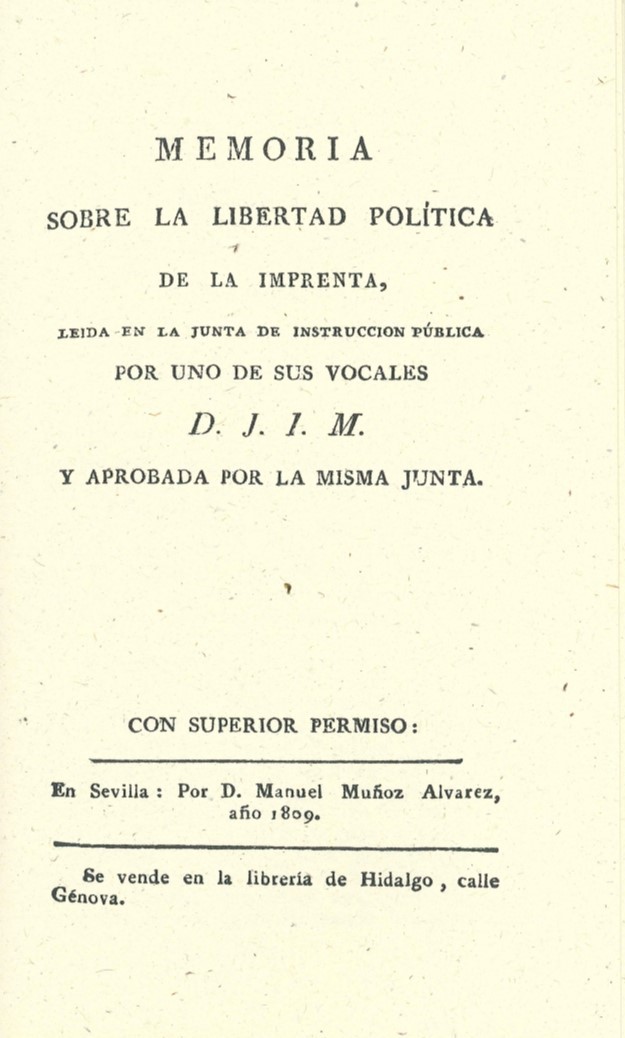

Approved as a collective opinion of the Public Instruction Board, even though not all its members agreed with it, on December 15, 1809, it was sent to the Cortes Commission. The Memorandum was printed in that month of December at the Seville establishment of Manuel Muñoz Álvarez and began to be sold, for general enlightenment, at the Hidalgo bookstore on Génova Street. It was a 32-page pamphlet that, curiously, was not signed with the name of its author but with the initials D.J.I.M.

In any case, although the content and dissemination of the Memorandum on the political freedom of the press allow us to now claim the pioneering role of José Isidoro Morales in this crucial issue of shaping liberalism in Spain, there is something perhaps even more relevant: it was not only Morales who wrote and gave birth to the Memorandum but also the author of the accompanying bill, which, although it was also sent to the Cortes Commission by the Public Instruction Board, was not printed. Fortunately, that project, in the handwriting of José Isidoro Morales, is preserved in the Archive of the Congress of Deputies. It was a fifteen-article project that constituted the draft on which the Cortes would later work. Therefore, the Project of the law on freedom of the press may have been a contribution from Morales greater than that which purely constituted his Memorandum, although, being a working document and not seeing the light in print, it did not become as known then or be as valued today. The bill was transcribed by Morales on December 14, 1809, and sent to the Cortes Commission, alongside the Memorandum, one day later.

Morales's ideas circulated and had a very broad echo, being the most direct precedent of the decree of November 10, 1810, by which the Cortes of Cádiz renounced prior censorship -except for matters related to religion, which the man from Huelva had not exempted- and recognized both institutions and individuals "the freedom to write, print, and publish their political ideas without the need for any license, review, or approval prior to publication." It was the first time in Spain that freedom of the press was decreed. José Isidoro Morales, despite taking two centuries to recognize his responsibility in this, can rightfully be considered the father of that freedom, now crucial in democracy.